October, 2013: I enter Isabela Muci’s studio and I see her walls. There are traces of tape and a variety of paint marks. From these walls she hangs and takes down her work, to see it at a distance once she has done. So, I think, she may want to retouch, or maybe erase, the perception of other beginnings. There is also a piece of wood covered with paint lumps, and a collection of paint brushes neatly placed, and also a faucet smudged with paint. There is a high easel with what seems to be a work in progress. From the floor to ceiling glass windows, light comes in making everything neatly visible, and I notice in a corner a constellation of staples. Just as they are, they suggest vague, volatile shapes. They must have held together drawings or drafts. I think that time –and its “labors”– provoke a great variety of discoveries, if and when there is a constant of attention and hearing, because everything passes and, if there is no one to notice, they might as well have never existed. But the studio, specially, if it belongs to someone who works with paint, is the place to leave traces. This is where the artist perceives her relationship with what she does, and where she can better speak about her work and her days.

October, 2013: I enter Isabela Muci’s studio and I see her walls. There are traces of tape and a variety of paint marks. From these walls she hangs and takes down her work, to see it at a distance once she has done. So, I think, she may want to retouch, or maybe erase, the perception of other beginnings. There is also a piece of wood covered with paint lumps, and a collection of paint brushes neatly placed, and also a faucet smudged with paint. There is a high easel with what seems to be a work in progress. From the floor to ceiling glass windows, light comes in making everything neatly visible, and I notice in a corner a constellation of staples. Just as they are, they suggest vague, volatile shapes. They must have held together drawings or drafts. I think that time –and its “labors”– provoke a great variety of discoveries, if and when there is a constant of attention and hearing, because everything passes and, if there is no one to notice, they might as well have never existed. But the studio, specially, if it belongs to someone who works with paint, is the place to leave traces. This is where the artist perceives her relationship with what she does, and where she can better speak about her work and her days.

–Alejandro Sebastiani Verlezza

ASV: Isabela, what is your favorite occupation?

ASV: Isabela, what is your favorite occupation?

IM: To wander about… it’s a state of meditation where connections, new meanings are established, mostly at a slow pace. Alchemists used to say that patience was one of the most important qualities of the soul, and that language is created in the digestion: both in the flow as in still waters.

ASV: I suppose you prefer some wanderings to others.

IM: In the studio, in dreams, in museums. These are intuitive states, almost magical. They don’t respond to logic. There are spaces within myself filled with works of art. Internal abysses that I feel are full, physical, like forces that integrate all past and present time –since I was a child until now- conscious and unconscious, very intimate experiences and processes that have made me understand that works of art are not just objects to be seen, but that also have power, they do things.

ASV: What happens in your dreams?

IM: Images that integrate with my visual discourse emerge and remain in time: as long as the mystery keeps them alive. Other times, I find in them formal solutions that slip away from me when I’m awake. So at night I tend to the calling. And the studio is the studio, the hat where the rabbits come from.

ASV: Tell me about your color palette.

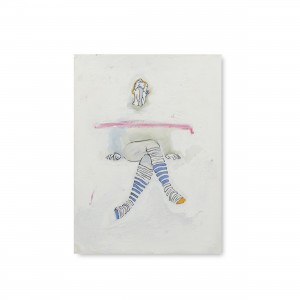

IM: The palette is something that prevails, determines the image and not the other way round. The color comes to me first, and then a series of complementary ones. If I start out with a water green, a red line will cut through –even if its just perceptible– that will create a visual vibration. The same happens between more subtle layers. The austerity of whites interests me, pushed by colors from behind. Like blood and heart beats, which can’t be seen but give life to the skin. And then the pure colors, the more pure they are, the more intense they will be. And that’s how I like to play, balancing between extremes.

ASV: How did you end up with those colors?

IM: Maybe they’re a resonance of the modern Europeans, those I feel live within me: Van Gogh, Matisse, Degas, Cézanne, Monet, Gauguin. Also the Fauvists and he German Expressionists. When I first arrived in Paris, they left an impact on me. The palette is a program that rarely leaves me, and is deeply linked to emotion. Just like music, color is a spiritual resonance.

ASV: What defines an artist’s training?

IM: Awareness of the process. Children come with a certain sensibility, an opening, a spontaneity. They may come with expressions of unexpected brilliance. But they’re not artists, they have no notion of continuity, nor perspective of time.

ASV: Has someone left a mark on your training?

IM: In Paris, I had a teacher and friend: Ralph Petty. He taught a course called “techniques and materials”. I learned about pigments; I had a glass mortar to emulsify the oils that I’d store inside metal tubes, and that I would open months later to check if the pigment and the linseed had reached the appropriate alchemy. I would stretch my frames, prepare my canvases with rabbit skin glue, and he would tell me: this is where the work begins. What he really was talking about was the active meditation as a way of encountering the creation, and he would guide me in the art of patience.

ASV: Why work with discarded objects?

IM: Because I think it’s like life, a constant recovery of oneself, to accept that fragility. But it’s also a provocation of the loss: sometimes I put the half finished pieces under the open sky. Under the sun, rain, night; I sand them, I observe how they behave, I intervene them, I move them back and forth.

ASV: The waste ground proposal, how do you relate to with?

IM: That which needs to be inhabited. It’s a constant journey that comes from dissatisfaction. And then there’s the rest: what we love and think we know. But there’s always more, and it’s very easy to take for granted something of importance unless you see it from a non-conforming point of view.

ASV: Why oils?

IM: For their aroma, greasiness, viscosity… deep as tattoos. Also for the intensity and translucent quality of the colors; for the time it demands at work. Oil is time to make, and at the same time it’s continuity.

ASV: What do you demand from the execution of your work?

IM: To not leave anything to chance. Respect in its nakedness. That the work upholds its dignity through time.

ASV: How do you compose your images?

IM: From my intuition and in the manner of a visual collage. It’s fragments –like memories– of images with emotional charge: losses and abandonment with which to reconstruct myself.

ASV: Let’s turn back a moment to your influences.

IM: I have always been interested in arte povera. The half torn cloths of Lucio Fontana would soberly tell me that something was happening behind the support. From early on, I was fascinated by museums where I’d discover objects and images that modified me, and I would discover myself in them. I was captivated by paint and also sculpture as an existential experience and outer appearance.

I look for that once I open the oil paint tubes. As of that moment, it’s as if I slip out of my body, come out from a suit. Already in the act of picking up the spatula –and spreading the paint on the palette– my breathing changes. I feel pleasure camouflaging myself in the viscosity of the matter: that subterranean or cavernous world, where the atmospheric pressure changes, the sounds of this world disappear, there is humidity and air currents, the walls move like waves. I feel grateful to be there, something awakens and my senses become sharp in a singular and intense manner. Braque used to say: “what is essential in art is what cannot be explained.”

ASV: What do you wish to offer as a teacher?

IM: To learn. The voices of my teachers have stayed with me throughout my processes. Even after all these years, I hear them, they guide me. They walk with me when I am by myself, rethinking formats, materials, themes, routines, rituals.

ASV: Do you remember any particular “lesson” form those teachers?

IM: Yes: the longer the recognition arrives, the better. I will have more time to be myself and to be separate from what others expect. The physical work is not missed. It’s in me. What is important is what happens to me during the process. Once sold, it has fulfilled its function, and maybe others will follow. In that abandonment a new experience occurs. Only by letting go, new findings occur. A new order appears. From this perspective, recognition is a relative notion.

ASV: Work without stopping, then.

IM: Yes, I find meaning in contemplation and the resonance of work.